Wartime Memories 2

History records that, for a period of eight months, from September 7th 1940 until May 11th 1941, Nazi Germany subjected Great Britain to a campaign of, intense bombing: Blitzkrieg. During which time the Luftwaffe carried out continuous air raids on London and other strategic targets across the length and breadth of the U.K.

What is not so well known though is that almost 11 months before that, on 16th October 1939, the first air raid on the U.K. had already taken place and that it had happened in Scotland.

*

1.1 THE INCIDENT

I came into this world in October 1934 and just short of 5 years later, in September 1939 I started school at Trinity Academy in Craighall Road in Leith, Edinburgh’s principal port.

On the 1st September 1939, Hitler invaded Poland and on 3rd September, Britain declared war on Nazi Germany.

Just over a month later a few residents of Edinburgh came uncomfortably close to becoming the first civilian victims of Hitler’s war on mainland Great Britain! And I was one of them.

Things were so different in those days. I had been going to school for just a few weeks and had proudly progressed from being escorted to and from school, to walking the short distance home on my own after a game of football in the school playground.

My mind-numbing experience occurred in Newhaven Road, while I was hurrying home from school thinking only of getting home for my ‘tea’. (evening meal)

Ratt- att -tatt -att -att.! Whooosh! And without warning the middle of the road to my left erupted in a splatter of dust, sparks and road chippings. Instinctively I flinched and cowered away. Before I realised what was going on; roaaaar….whoosh.….an aeroplane screamed over my head, at rooftop height, only to disappear in an instant, over the buildings ahead of me, heading towards the centre of Leith. All I had time to see, before I was buffeted by a rush of disturbed air full of the acrid smell of exhaust fumes, was that it had been one of our planes.

When I recovered enough to look around me, the only other person I could see was a woman protectively draped over a pram and looking up at the sky. Almost as soon as I saw her, she straightened up, dusted herself and the pram down and scampered off northwards, pushing the pram, containing her precious charge ahead of her before disappearing round the corner into Summerside Place.

Totally confused by what had just happened, I apprehensively went to where I had seen the sparks flying up from the tram-railed granite sett roadway.

For some distance along the middle of the road the cobbles were broken, cracked and scarred. Strewn over a wider area were fragmented, white powdered chunks of stone and earth.

Among this debris, I could see a few fragments of smouldering, flattened grey, metal. My curiosity aroused, I gingerly prodded one of them with the toe of my shoe. It looked vaguely familiar. Bending down I picked it up, only to drop it immediately. It was burning hot!

I shuffled it around with my toe until I judged it was cool enough to handle. A closer inspection proved my earlier assumption had been correct; it was a bullet, its formerly pointed nose squashed obliquely flat.

I had been shot at. But by whom and why me? Our planes are supposed to shoot at Germans!

I took my souvenir home, hid it away and said nothing about it to my parents or anyone else for that matter.

*

The memory of the event remained stowed away in the dark recesses of my brain until initially, in the early 2020’s, a lady described in conversation, how her brother had experienced a comparable episode around the same time as I did. And at a place not too far away. Shortly after that, I read a newspaper article about how Richard Demarco had suffered a similar episode in Portobello. Everything was now beginning to come together.

Finally, everything was confirmed when I read Henry Buckton’s excellent book ‘The Birth of the Few’. As, on page 11, he quotes “A mirror in the Lord Provost’s residence received a direct hit from a machine-gun bullet.” The Lord Provost at the time was Sir William Y. Darling, and I knew that my escapade had happened right outside his front gate.

As, I was there!

The site of the event. Newhaven Road runs across the bottom left corner. (I was walking from right to left.) In the bottom left corner is part of Sir William Y. Darling’s front gardens and on the opposite side of the road are the Victoria Park Bowling Greens and Clubhouse.

Now I wanted to find out more about this raid and to try to establish who had been responsible for shooting at me?

What follows are the bones of what my investigation unearthed;

My first instinct led me to the newspaper archives, but they proved to offer little in the way of detail so I turned to using well tried and familiar search engines on the internet.

2. THE BACKSTORY TO THE LUFTWAFFE’S PRE WAR ACTIVITIES

2.1 HITLER’S NAZI’S GATHER INFORMATION

During the 1930’s Hitler’s Germany had systematically amassed a huge amounts of photographic information about the countries it saw as a threat to itself or was considered rife for acquisition at some time in the near future.

To this end, naval sailing ships, crewed by cadets, paid frequent visits to European ports, each cadet armed with a camera and given precise instruction on what to photograph. Similarly, Lufthansa and other German planes on scheduled flights took countless aerial photographs of any areas of strategic importance they flew over.

One area of particular interest to them was the Firth of Forth in Scotland where The Royal Navy had an important dockyard at Rosyth.

By 1939, with the likelihood of war increasing, almost by the hour, the Luftwaffe had already begun to fly their own reconnaissance sorties.

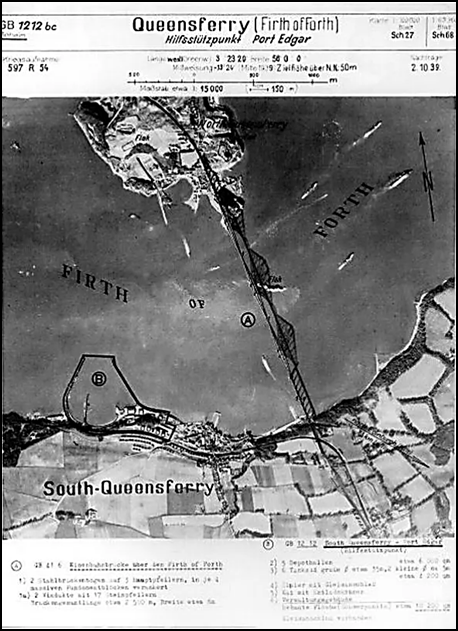

Below is a copy, and enlargement, of one of these photographs taken during a sortie on 1st October 1939 which shows the Rosyth Dockyard and the area around The Forth Railway Bridge.

An early Luftwaffe reconnaissance photo taken on 1nd October 1939 by a Dornier 17P, two weeks before the first raid of WW2 on Britain.

Detail of Forth Rail Bridge, highlighted by its shadow, a steam from train crossing and ships at anchor.

(The plane that took this photograph was damaged while landing at Fp. Uetersen, a Luftwaffe base 20 km NW of Hamburg)

2 .2 PRELUDE TO GERMANY’S FIRST AIR RAID ON BRITAIN

In the early hours of the 16th October, from the Island of Sylt which lies off the North Sea Coast of German occupied Denmark, the Luftwaffe were preparing to launch its first air raid on Britain. Their principle target would be the British battleship and pride of the fleet, H.M.S. HOOD, which they believed to be anchored in the Firth of Forth about 10 miles west of Edinburgh.

If they could sink her they would not only deprive the Royal Navy of its most formidable battleship but score a spectacular first strike in the recently declared war and give them an enormous propaganda coup. Unfortunately for the British no one in the U.K had the tiniest inkling of what was about to happen!

2.3 THE RECONNAISANCE FLIGHT FOR THE RAID

At 09.20hrs, on the 16th October 1939 the ‘Chain Home’ Aircraft Direction Finder station, the forerunner of radar, at Drone Hill near Coldingham, detected two intruders heading towards them from over the North Sea.

At 09.45hrs, a local Observer Corps report placed an unidentified aircraft, at high altitude, on a south-westerly course, over Dunfermline heading for Rosyth, and another one in the Borders area near Galashiels.

Three minutes later, at 09.48hrs, the three Spitfires of Blue Section No. 602 Auxiliary (reservists) Squadron (led by Flight Lieutenant George Pinkerton) based at Drem, in East Lothian, were sent aloft to patrol the area around the Island of May, at the mouth of the Forth Estuary.

Heinkel He 111.

Above: Early camouflaged Spitfires

George Pinkerton, later Group Captain, OBE, DFC.

Archie McKellar

From Cuthbert Orde’s book – Pilots of Fighter Command, 1942:

At 10.08hrs, the lookouts on board the light cruiser H.M.S. Edinburgh, sitting at anchor in the estuary, spotted a Heinkel He 111 and not long after that a plane was seen flying over Drem.

Around the same time, Blue Section who had been patrolling the skies over the Island of May for some 20 minutes, were now ordered to move southward in the direction of Dunbar to investigate. Almost right away, they spotted a Heinkel He111.

Pinkerton ordered Blue section to take up an attack formation. However, just as he said that, the German bomber made a sharp turn to port and escaped into the clouds. Pinkerton and another of his pilots’ Archie McKellar, while still some distance away, fired at the fleeing German aircraft but inflicted no damage.

The enemy plane – one of the two Heinkel He 111 twin-engine medium bombers of Oberst Robert Fuchs’s Kampfgeschwader 26 from squadron KG2i fitted with cameras, had been on a flight to reconnoitre and photograph the afternoon’s target anchored in close proximity to the Royal Navy dockyard at Rosyth, got safely back to its home base at Westerland, on the Nazi occupied island of Sylt which was, at that time, the nearest Luftwaffe base to the UK.

Oberst Robert Fuchs

Unknown to the British, the damage had already been done as the crew of the Heinkel had radioed back a situation report of the target area and crucially, the names of the ships at anchor in the Firth. Including, mistakenly- as it turned out- the battleship H.M.S. Hood.

By the time Blue Section had touched down on their home field at 10:44, their morning sortie had already taken its place in history.

So it was that at 10:21hrs, on the morning of the 16th October 1939, Lt. George Pinkerton of 602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron, stationed at Drem in East Lothian, became the first R.A.F. Auxiliary fighter pilot to attack a German aircraft over Britain when, in his Spitfire. He fired 720 rounds from his eight .303 Browning machine guns at a German reconnaissance plane over the Isle of May in the River Forth Estuary.

This encounter is also recognised as being –

the first combat engagement by a Spitfire.

the first shots fired during a dog fight over mainland Britain.

However, as we shall see, his record breaking achievements that day were just beginning.

Note: A fully fuelled and armed Spitfire had approximately one hour of high combat flight and around 17 seconds worth of ammunition.

*

3 THE FIRST AIR RAID ON MAINLAND BRITAIN 16th October 1939

A contemporary artists’ impression of the Battle

George Shoolbread Oil on hardboard 1935. (The work of a member of my wife’s family.)

It must be understood that the passage of time has clouded what has been recorded about the BATTLE OF THE FORTH. As a result information available is now littered with confusing errors, genuine misunderstandings, conflicting assumptions and downright poor misinterpretations.

The fact that the incident happened in wartime, when the release of information to the public was severely restricted, can be blamed for some of this but it does make modern day research difficult and often only provides the researcher with less than satisfactory answers.

Because this event involved a goodly number of aeroplanes, took place over a fairly long period of time and was flown over a sizeable area of territory, the narrative will be confined to matters that had some bearing on the writer’s involvement.

The anatomy of a 4man crew Junkers JU88 bomber.

3.1 THE SEQUENCE OF EVENTS.

At Westerland, when the report came in from the mornings’ reconnaissance flight, KG 30‘s officer leading the raid Hauptmann Helmuth Pohle took his bombers off standby and started to get his raiding party of 12 JU 88a bombers into the air.

Their principal target was HMS Hood and the raiders were scheduled to attack her in 4 waves of 3 planes.

The first wave, led by Pohle himself, took off at 11:55hrs and was followed almost immediately by the second wave, led by Oberleutnant Hans Storp, his second in command.

Oberleutnant Hans Storp,

(Hospitalised in Edinburgh Castle after the raid,)

Within minutes all twelve bombers were airborne and heading for Scotland.

The plan was to cross the North Sea at 22,965 ft. (7000 m), make landfall near Berwick upon Tweed, then fly west to cross the Scottish border before turning north to carry out the attack.

Because of the usually long distance the planes would have to travel and to allow for the extra fuel needed to do this, each aircraft’s payload had been reduced to two 500kg bombs.

THE RAID

3.1 FIRST CONTACT

At 14:20hrs, the Observer Corps reported enemy aircraft over East Lothian and shortly afterwards, Turnhouse ordered 602 Squadron’s Blue Section commanded by Lt. George Pinkerton, already a hero of the day, to scramble from Drem and investigate two unidentified aircraft flying over Tranent.

At 14.27hrs, an anti-aircraft battery situated in Dalmeny Park – close to the Forth Bridge – reported some German aircraft flying up the Firth of Forth at a height of 10,000 ft. (3050 m).

At 14:30hrs, Pinkerton, having found nothing over Tranent, was ordered to fly north to patrol the Firth of Forth.

At the same time, Spitfires of 603 Squadron’s Red Section (led by Flight Lieutenant Pat Gifford) were scrambled, with orders to head east, towards East Lothian.]

Flight Lieutenant Pat Gifford.

As the Spitfires were getting into the air, Hauptmann Helmuth Pohle had arrived at the target area only to see that his target, which had earlier been identified as The Hood, was in fact the Repulse and that it was now sitting in a dry dock. This meant that the principal objective of the raid could no longer be achieved. So he decided to change the focus of the raid to inflicting as much damage as he possibly could to the British warships lying at anchor nearby. This included a pair of ‘Town’ class light cruisers: H.M.S. Edinburgh and H.M.S. Southampton, the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Furious, the destroyers H.M.S. Jervis and H.M.S. Mohawk which would bear the brunt of the surprise attack.

Up to this point the raiders had met with no airborne opposition

At 14.35hrs, Pohle commenced his attack and during the course of his first dive, the top part of his cockpit canopy broke off, taking with it the rear-facing machine gunner OGefr. Kramer.

He was the first human fatality of the battle.

At 14:38hrs, three minutes after the attack began, orders for the defenders to open fire were at last given and every anti-aircraft and machine gun on land and all of the ships guns that could be brought to bear opened up.

Meanwhile, the next wave of attackers, led by OLt. Hans Storp, arrived on the scene.

Somewhere around 14:45hrs, George Pinkerton, spotted Helmuth Pohle’s already damaged aircraft circling over Inverkeithing and he and his wing-man Archie McKellar, immediately attacked, killing two of the German plane’s crew and incapacitating both of its engines.

Pohle now headed for the sea near Crail and ditched three miles off of Fife Ness.

Red Section under Flt. Lt. “Patsy” Gifford, fatally damaged Storp’s Ju-88 bomber near Cockenzie and the German aircraft, crashed into the Forth 4 miles offshore. Very soon after which Flight Lieutenant George Pinkerton of 602 Squadron, bagged Pohle’s off Crail.

About 25 minutes after Pohle’s plane went down, another Ju-88 bomber was seen approaching from the outer reaches of the Forth. It had escaped interception up to this point, as the ground observers had initially thought it to be a friendly Bristol Blenheim (an easy mistake at the time, as the two were somewhat similar and the Ju-88 was a brand new aircraft and almost totally unseen by British eyes this early in the war).

At 15.25hrs, his plane, having received the revised target signal, commenced a ferocious attack on the destroyer HMS Mohawk, sitting at anchor justoffshore near the fishing village of Elie & Earlsferry, inflicting a significant amount of damage, and killing 13 ratings and two officers.

Her mortally wounded captain, Commander R. F. Jolly, only succumbing to his wounds once he knew his ship was in dock and safe.

Commander R. F. Jolly

By 15.45hrs, the battle was over

It is worth noting that no public air raid warnings were issued or sirens sounded throughout the period of the conflict.

*

3.2 THE BUTCHERS BILL.

Pilot OLt. Hans Storp and his crewmen Hugo Rohnke and Hans Georg Heilscher were saved and sent to the military hospital at Edinburgh Castle. They were the first German military prisoners in Britain of WW2. His rear gunner who had been killed before the plane crashed and his body was not recovered,

All of the Spitfires and their ‘weekender’ auxiliary service pilots got back to base safely.

Nine of the 12 German aircraft got back to base. Two were shot down during the raid while the third limped back over the North Sea to Norway, where all of its crew died while attempting to land. It is not known whether this aircraft was damaged, by spitfires or anti-aircraft fire.

During the course of the raid Germany lost 3 of its 12 planes and 8 of its 48 airmen lost their lives. Another undisclosed number were wounded and a few others taken prisoner.

24 British sailors were killed and 44 wounded in the attacks on the British Navy’s ships

In the final engagements over Edinburgh, rounds did cause damage to property and a painter working in Portobello was hit in the stomach but recovered.

Incidentally, the Forth Rail Bridge – often mistakenly reported as being the principal target and around which the battle raged – came through the conflict completely unscathed.

4. CONCLUSIONS

4.1 WHO SHOT AT ME – FRIEND OR FOE

Although nothing is certain, I have, by putting together some of the recorded sightings of a German bomber passing over the North Leith area, on its flight from Forth Bridge to where it finished up close in the Port Seton (vis. over Granton, Newhaven Road, Pilrig Park, Taylor Gardens and Portobello) – which after taking into account the evasive action the bomber would have taken – has provided me with enough information to regenerate its likely flightpath, in the course of which, I came under fire.

After cross-referencing and deliberating over all of the information I have to hand, it is my considered opinion that it was Oberleutnant Hans Storp’s Ju.88 that over flew over me on Newhaven Road, at just after half past two that day.

It then follows that the Spitfire engaged in that incident was Flight Lieutenant Pat Gifford’s.

But whose bullet did I find?

Operational combat spitfires of the time were fitted with 303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns, while the Junker 88’s had MG 17 machine guns developed in 1936 which fired the standard Mauser 7.92mm cartridge.

Unfortunately with no markings on the damaged bullet I found and with the size of both of the combatant’s ammunition being within 0.2mm of each other, it was impossible to determine whether friend or foe had fired the offending bullet.

However, accepting that the normal attack orientation, makes it more likely that it came from the Spitfire, firing down from behind. Consequently, there is a high probability that it was one of Gifford’s while he was shooting down on Storp.

I am therefore fairly comfortable that my uncomfortable experience that day was the result of ‘friendly fire’ executed by one of the heroes of the day.

SOME INTERESTING ASIDES

Some World War II firsts established during the raid:

The first aerial dogfight over Britain.

The first ‘kill’ attributed to a Spitfire over Britain.

The first German aircraft to enter British airspace.

The first Luftwaffe attack on the British Isles.

The first German aeroplane brought down on British soil.

The first Luftwaffe casualties.

The first British civilian casualty. (A steeplejack/painter in Portobello was wounded.)

HMS Hood was sunk by the Bismarck in the Denmark Straight between Greenland and Iceland, on 24th May 1942 and lost of all but 3 of her crew of 1,418.

Both H.M.S. Repulse and her sister ship H.M.S. Prince of Wales (on which my cousin served) were sunk by Japanese aircraft in the South China Sea off the east coast of the Malaya on 10 December 1941. Repulse lost 840 of her crew and the Prince of Wales 327 crew.

H.M.S. Mohawk was sunk by torpedoes fired by an Italian destroyer in 16 April 1941 in the Mediterranean somewhere off the coast of Tunisia with the loss of 41 of her crew.

–*–

Acknowledged Sources

The Birth of the Few by Hendry Buckton

The Last of the Few by Max Arthur

The Forth at War by William F. Hendrie

Edinburgh Traces by Ian Garden

The Thread About A Day Of Firsts; website by Andy Arthur.

That’s it Folks!

Johnny Jones

I would love all this information in a book. Great reading.

Gwen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How absolutely extraordinary! This was a great read – glad that you survived the day – lends a new light to all that is going on in the world at the moment. Linda x

LikeLike

What an amazing personal account and historical research. You have lived through too many wars. When will humanity learn?

LikeLike

Excellent story 💜

LikeLike

How amazing that you experienced that. My father in law spent most of the war in a German prisoner of war camp in Eastern Germany – he was in the Gordon Highlanders. Small towns in the North East of Aberdeenshire were regularly bombed because of the fish canning industry.

Great post on our modern history.

LikeLike

Enjoyed the read. I know a little about German Gotha bombers WW 1 and raid. Have about fifty 1/72 scale WW 1 model planes on shelves. Read about WW 2 German V rockets the other day.

LikeLike

Fascinating to learn about your collection, have you any photographs?

Thanks for your comment, Johnny

LikeLike

What a fascinating story. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Thank you Christopher.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Johnny, what an extraordinary account—equal parts vivid memoir and meticulous historical detective work. Your firsthand experience on Newhaven Road is related with chilling details, especially given your age. This investigation reads like a wartime mystery solved with care and clarity. Thank you for preserving and sharing this personal window into a pivotal moment in British history. Cheers, Mike

LikeLike

Thank you, Mike, for your comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A fascinating account Johnny, and well done with the research. Thank goodness they missed you!

LikeLike

Thanks Peter, I am glad too!

LikeLiked by 1 person