The Edinburgh Life Magazine is currently publishing a series of black and white Aerial Photographs taken in 1930 and comparing them to a series of my colour photos taken, from the same point of view, in 1993. This is the third and final post supplementing these articles.

The information provided and opinions expressed here are the author’s personal interpretation of the featured events he has accessed. It must also be recognised that modern research methods are continuously finding and re-interpreting new older information.

1930 Edinburgh photograph on the left, and the same location photographed in 1993.

TYPES OF IN-FLIGHT PHOTOGRAPHIC IMAGES

A photograph, as seen through one lens, shows a single-point of view and can therefore, not convey any true spatial perception. But, by using two lenses to imitate the eyes, we produce the conditions to create a space image.

Aerial photographs are generally categorised as being either oblique or vertical.

Oblique Images are taken at an angle, allowing sunlight to highlight the physical features on the ground through shadows. These images are a true scale representation of the scene.

Vertical Images are taken with no deviation from the perpendicular (i.e. looking straight down).

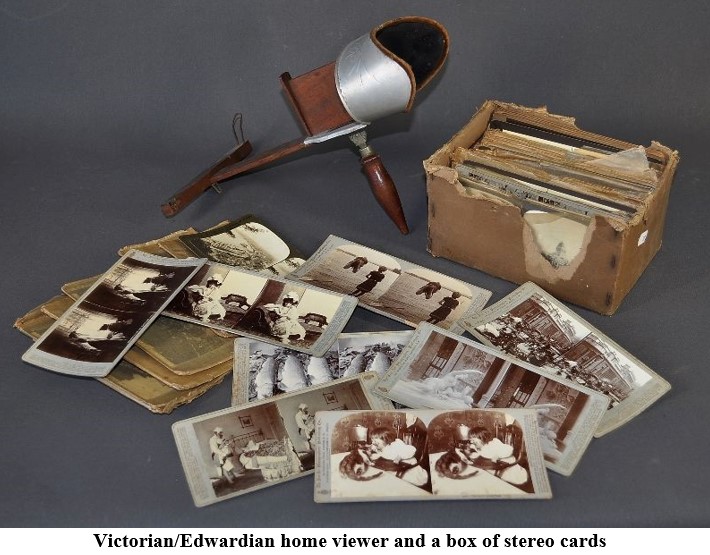

For either form of image a three-dimensional effect can be achieved by taking overlapping pairs of photographs, from slightly offset positions, and viewing them through a stereoscope.

One should be aware however, that oblique images are closer to a true representation of the differences in height, whereas vertical images produce a marked degree of vertical exaggeration.

Nevertheless, this facility, of being able to identify differences in height, has made both types useful in searching for previously unknown archaeological sites.

1 EARLY HISTORICAL LANDMARKS

The first explanation of our capability to see a flat image in three dimensions is attributed to Euclid, who in 280 B.C. recognized that our perception of depth of view is obtained when each of our eyes simultaneously receives a dissimilar image of the same object.

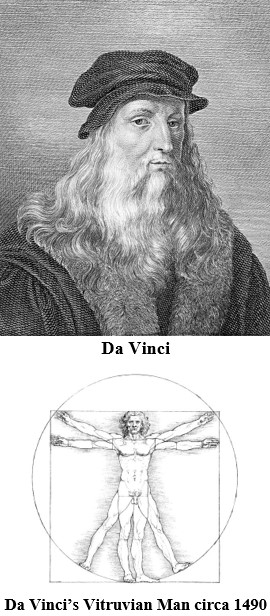

Then Leonardo da Vinci when, in 1584 who was studying the perception of depth of view to produced paintings and sketches, demonstrates that he too had a clear understanding of the effects of shading, texture and viewing point projection.

Far from being a development of photography, the idea of stereographic perception is even older than the invention of the photograph.

The word “stereo” comes from the Greek and means “relating to space”. Nowadays, even although the term was originally allied to stereoscopic pictures – either skilfully drawn or photographed – when stereo is mentioned, the first thought that comes to mind, is usually associated with sound. i.e. stereophonic.

2 HOW IT ALL WORKS

We exist in a three-dimensional, spatial, environment and cannot move within it without us being aware of our own sense of space, the awareness which is predominantly provided by our sense of sight. To orientate ourselves in this space, we primarily use our eyes to determine perception of depth, graduation of colour, texture contrast and movement.

The lenses in a healthy human beings’ eyes project two slightly different images onto our retinas which the brain then transforms into a single spatial representation.

A photograph taken from a set position can only show a single-point of view, as seen through the camera’s one lens. Therefore, it cannot convey any sense of true spatial perception.

But, by looking through two lenses positioned side by side, we can imitate the image our brain sees as that of one produced by two eyes and thus create the conditions necessary to give us a spatial image in our brain.

More commonly/commercially referred to as three-dimensional – 3D – pictures,

3 THE INVENTORS

The three dimensional flat image story really starts when, in June 1838, Professor Sir Charles Wheatstone, of Wheatstone Bridge electrical circuitry fame, published a scientific paper in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (Volume128, pages 371-394), describing how we are able to see images in 3D. Click here to read.

To support his ideas, he did some simple 3D drawings and to allow the drawings to be seen in three dimensions, invented, a device he called a reflecting mirror stereoscope. When these drawings were viewed through this instrument, he was able to show that the brain combined the two images and produced a perception of depth of view. The principles of this instrument, The Wheatstone Stereoscope, are still used in radiography today.

Wheatstone’s original mirror splitter apparatus – stereoscope – (above) was a fairly large, and cumbersome instrument, but it did have the advantage of allowing large images to be viewed.

Throughout Europe and America during the 19th century, Photography, in general, progressed very rapidly and Wheatstone’s latest idea was eagerly studied by photographers who then enthusiastically purloined, adapted and developed it to meet their own needs.

Wheatstone made a number of different models of his stereoscope, including one which folded neatly into a box. (His original instruments are preserved in the archives of Kings College, London, where he worked.)

In the following year, 1839, both Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in France and William Henry Fox Talbot in Britain, came up with their own slightly different three dimensional photographic processes. Daguerre’s could be viewed on a copper plate with a very thin silver layer, Talbot’s on paper.

Hence, methods for viewing three dimensional images were in existence even before the invention of photography.

In 1840, Wheatstone wrote to Fox Talbot, and Antoine Claudet, a licensee of the Daguerreotype process working in London, and suggested that they make some stereoscopic photographs.

Fox Talbot made Calotype stereoscopic pairs of photographs and sent them to Wheatstone in the same year. These Fox Talbot images are the first photographic three-dimensional images ever made. (The correspondence between the two men still exists but, unfortunately, the images have been lost.)

There are those who believe that Claudet was the first to make Daguerreotype stereo images, but his were produced in 1842, a year after Fox Talbot’s work.

Around this time a great rivalry existed between British and French photographic enthusiasts, but there was also a considerable amount of collaboration as well.

When compared to Fox Talbot’s Calotype process, the French Daguerreotype polished copper plate images, offered a far superior reproduction of detail, but were not easy to reproduce, which from a commercial point of view, was a considerable disadvantage.

4 THE VIEWING EQUIPMENT

THE USE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC LENSES TO PRODUCE 3D IMAGES

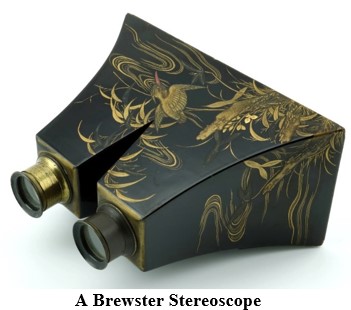

The brilliant St Andrews University physicist Sir David Brewster (1781–1868), can be credited with the invention of the first lens-based stereoscope in 1849. This viewer was a far more compact device than the fairly bulky Wheatstone’s apparatus.

Brewster gave the order to manufacture this device of the Dundee optician George Lowden.

Lowden made several of these instruments which, Dr. Brewster, in his enthusiasm to promote his discovery of stereo photography, gave away to members of the English nobility.

However, a difference of opinion, about the quality of the lenses Lowden was using, saw Brewster transferring the manufacture of his invention to the French firm of Duboscq et Soliel in Paris and it was one of their models that Brewster demonstrated during the 1851 Great Exhibition in London.

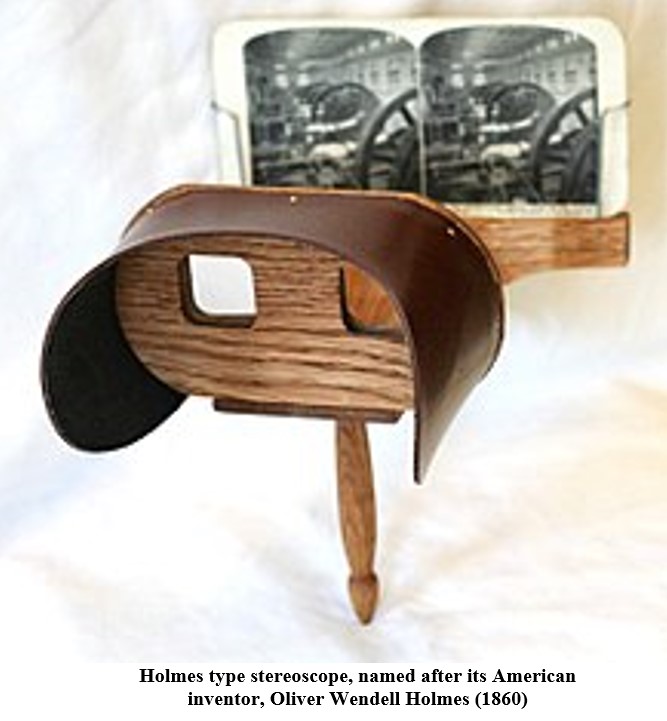

In around 1860, Holmes, an enthusiastic polymath, invented the “American stereoscope“, Later he wrote an explanation for its popularity, stating: “There was not any wholly new principle involved in its construction, but it did prove so much more convenient than any of the hand-instruments currently in use,. So much so that it gradually drove them all out of the field,” – at least as far as the Boston market was concerned.

Rather than patenting his hand ‘stereopticon’ and profiting from its success, Holmes gave this idea away.

However the first real thrust to commercial stereo photography was given by Queen Victoria who, during her visit to the London World’s Fair at Crystal Palace in 1851, was so entranced by the stereoscopes on display there, that her widely reported enthusiasm for three-dimensional photography soon saw it becoming a popular form of home entertainment, world-wide.

(In 1856, Brewster – who incidentally, was also the inventor of the kaleidoscope – reported sales of over half a million stereoscopes.

Then in 1893, the first projection of a stereoscopic image was achieved by John Anderson, of Birmingham, He projected the images onto a screen of aluminium foil, through Nicol prisms, or tourmaline crystals, (naturally occurring polarizers). When viewed through matched polarising filters, the audience could see 3D images in the same manner as those still used in Stereoscopic Society and International Stereoscopic Union meetings today.

In the early days, stereoscopic images were obtained by moving the camera sideways about 62mm and taking a second view of the same subject from that slightly different position. This was fine as long as nothing in the image moved during the interval between taking the images.

A number of various ingenious contraptions were devised which enabled the whole camera to move the required distance and thus allowed early stereoscopic pairs of photos to be taken.

In 1853 Latimer Clark was one of the first to demonstrate a frame which moved the camera the required distance to take sequential stereo pairs.

The Manchester photographer John Benjamin Dancer patented a twin lens stereo camera in 1853, which he offered for sale in 1856.

In 1854 John A Spencer demonstrated a double width camera incorporating a moveable lens for taking sequential stereo pairs. The camera was fitted with an internal membrane separating the two images.

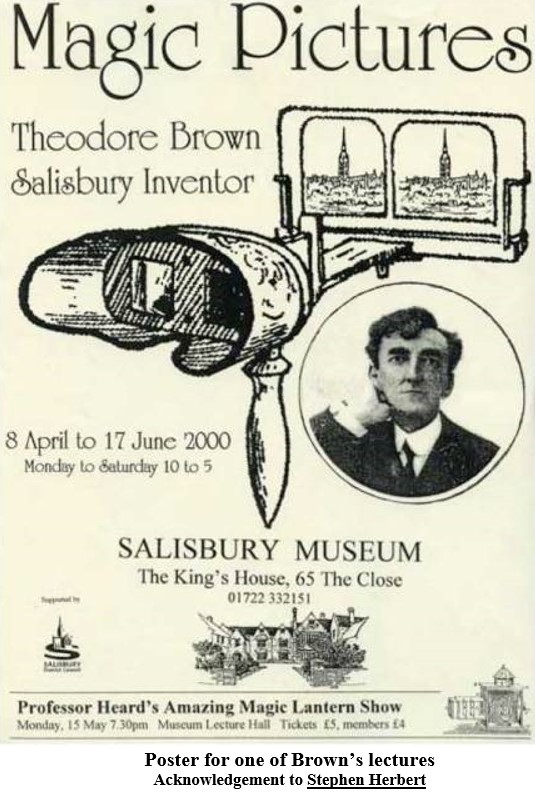

In the 1890s a Salisbury based engraver named Theodore Brown (1870 – 1938) who, over the years, had developed a fascination for optical toys, i.e. photography and stereoscopy, invented a system of mirrors attached to a single lens camera that created twin fields of view, thus enabling a stereoscopic image to be produced from a single lens camera.

5 THE MASS PRODUCTION OF STEREO IMAGES

The most prolific producer of early of stereo views for general distribution was the London Stereoscopic Company, founded in Oxford Street, London in 1854. This company employed many famous early photographers, including William England, William Russell Sedgefield, and Thomas Richard Williams and produced 350 stereoscopic views of the Crystal Palace Exhibition.

Around the same time, in America, Strohmeyer and Wyman, whose main distributor was Underwood and Underwood of New York, was the most prolific publisher.

By 1856 the London Stereoscopic Company proudly advertised that they held in stock over 10,000 stereoscopic images, the largest in Europe. However, the fortunes of the company declined over the years and they eventually sold their stock to Getty Images. The company closed in 1922.

In 1854 Negretti and Zambra Co. obtained the rights to publish stereo views of the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, South London and later sponsored Francis Firth’s expedition to Egypt, Nubia and Ethiopia, publishing many of his stereo views. They also published stereo views of Java taken from 1857 to 1863 by Walter B Woodbury, inventor of the Woodbury photographic process. They also sponsored Pierre Rossier to travel to China, Philippines and Thailand and on his return, published his stereo images, the first stereo views of those countries to be published.

In 1857 they manufactured a ‘Magic Stereoscope’, containing additional lenses giving greater magnification at the turn of a button. This instrument was fitted with an adjustable stand for desktop viewing and its base was elaborately decorated. Later the company diversified into the manufacture of barometers and other scientific instruments.

In 1858 the first book illustrated with original stereographs was published in London. This book, by the astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth is entitled “Tenerife, an Astronomer´s experiment: or specialities of a residence above the clouds”.

In 1862 Another later large exhibition was held in London, The International Exhibition, or the Great London Exposition. The then London Stereoscopic Company organised a display of stereoscopic views by famous stereo photographers William England and William Russell Sedgefield. During the course of the Exhibition, the company took in an average of £800 per day by selling stereo views.

Over the years many independent stereo photographers produced quality work; including Francis Bedford who sold sets of images of a fair number of the English counties and George Washington Wilson of Aberdeen, famous for the spectacular detail picked out in his interior shots. Roger Fenton produced many fine stereo images of the Crimean War which brought a stark sense of the reality of the conflict into the home.

Regrettably, many of the earliest stereo views do not show the name of the photographer; some only giving the site and date of the photograph, written in hard to read pencil on the back. There is also a significantly large number of stereo images that provide no clue as to either the location or the photographer. This anonymity of identity was probably used to avoid prosecution as both the Daguerreotype and Calotype processes were patented in Britain.

*****

In 2008 Brian May, guitarist of the rock group Queen, resuscitated the London Stereoscopic Company. He then undertook a study of the images of TR Williams, particularly those in the “Scenes From Our Village” set and by meticulous and diligent detective work, identified the village shown in these image to be Hinton Waldrist, in Oxfordshire and showed that many of the existing buildings in the village could still be clearly identified as the same ones illustrated in the TR William’s pictures.

In 2009, Brian, along with co-author Elena Vidal published these images in their book “A Village Lost and Found”. Which contains, for comparison, superb reproductions of the original tinted stereo images together with some present-day images of the same subjects.

Several other books containing reproductions of old stereo photographs have also been produced by the new London Stereoscopic Company.

Note: From the 1850’s onwards another successful way of producing 3D images was also being developed and one that led to the production of an effect that showed moving images. This was the Anaglyph 3-D which was the result of experiments carried out by the Frenchman, Joseph-Charles d’Almeida.

In which, by using red/green filters, colour separation took place. These early anaglyphs were displayed by using glass stereo lantern slides.

It was William Friese-Green who, in 1889, created the first 3-D anaglyptic motion pictures and which first went on show to the public in 1893.

END NOTE

“By the early 20th century other developments were taking place, such as the arrival of moving images, when the moving images started talking and later, with the development of computer generated Virtual Reality, when the observer moved from outside the object to being inside it; stereo photography fell from mainstream interest. It was kept alive by dedicated enthusiasts in stereoscopic societies in UK and worldwide. Interest in stereoscopy blossomed again in the 1950s and 60s with early 3D anaglyph films but fell away later. Now Digital 3D, including 3D TV, presents further opportunities for 3D enthusiasts to bring stereo photography to wider public interest”.

- Colin Metherell, Chair, Stereoscopic Society, 2017.

However, this branch of the subject is beyond the scope of this article.

WE ARE NOW AT THE END OF A THREE PART POST AND IF YOU HAVE STAYED WITH ME THIS FAR, THANKS FOR LASTING THE COURSE.

______________****______________

N.B.

A recent published interesting and informative book written and produced by Peter Blair has come to my attention and is well worth taking a look at in my opinion

It is, “Scotland in 3D A Victoria Virtual Reality Tour.”

ISBN 1-978-5272-7

For further information go to http://www.scotlan3D.com

Postscript

KEEP A LOOK OUT FOR MY NEXT INTERESTING POST

Johnny Jones

Hi Johnny, thanks for the great overview of a wonderful photographic technique which still surprises and amazes us today. Many thanks for the plug for my book! all the best, Peter Blair

LikeLike

Oh! This is so interesting – although it’s making me slightly cross-eyed-migrainey! LOVE the fort in Inverness – that is some WOW architecture there! Great post, regards, Linda 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks Linda, I can empathise about the headaches from putting this together in sort of order!

Take care

Johnny

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Johnny – have the best week ever! xx

LikeLike

*eyes glaze over* I absolutely LIVE for this stuff. It’s like you plucked my fascination with history and photography from my brain directly!!!

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. More to come on this subject soon.

Best wishes, Johnny

LikeLike

I sincerely thank Mr Johnny Jones who in his treatise on stéréoscopy of October 8, 2024 mentions Joseph Charles D’Almeida for his work on Anaglyphs ( Report of the sessions of the Paris Academy of Sciences of July 12, 1858) ; Mr. Joseph Charles D’Almeida is the Founder of the Journal of Theoretical and Applied Physics in 1872, also he played a major role in the creation of the Société Française de Physique in 1873 ( The premises were located from 1880 in 1961 in the Hôtel de l’Industrie, Place Saint – Germain des Prés in Paris). Source : ” 150 years of the French Physical Society ” published by Éditions EDP Sciences, June 30, 2023. Comments by Franck d’Almeida.

LikeLike

View Master, such good memories! 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Johnny

Thank you very much for providing all this information and the history of stereo photography.

Wishing you a wonderful weekend.

The Fab Four of Cley

🙂 🙂 🙂 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great undertaking!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I bought a 3D TV some years ago, thinking it was the way they were moving – they didn’t! However, it has the facility to show normal TV pictures as virtual 3D. It is fascinating to watch sport, particularly athletics, as it’s as if they are jumping in and out of the TV.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember the old View Master from the 1960s where you could look at images from paper reels through the viewer and you could see 3-D images before you.

LikeLiked by 3 people