THE BACKSTORY TO My book – Featured in the Edinburgh Life magazine September/October 2024

Old EDINBURGH: Views from above – Published in 2002 by Stenlake Publishing – www.stenlake.co.uk. – Whose editor said that, “Of all the books we have published this one is one of my favourites.”

THE 1930 BLACK AND WHITE OBLIQUES

In the late 1980’s a quantity of glass plate negatives were found in a Lothian Regional Council building that had formerly housed the offices of the City of Edinburgh Corporation. It was evident that they were fairly old.

The images were clearly recognizable as being views of Edinburgh as seen from above. However the provenance of these glass negatives was unknown, but the fact that they were found in the Council offices suggested that at some time in the past they had almost certainly been the property of and very likely commissioned by the old City of Edinburgh Corporation.

At the time when the photos were found Bill Roberton of Aberdour, photographer and railways enthusiast, was working at the Royal Observatory, in Edinburgh making 14 inches square facsimiles from glass plate negatives of a survey of the skies in the southern hemisphere, taken by the Observatory’s telescope in Australia.

One of Bill’s clerical assistants, whose husband worked for Lothian Regional Council, asked Bill if he could do something to preserve the images shown on these important glass plate negatives of the City

Bill converted the glass plates into half plate standard photo-negative positives. These were then passed on to the principal librarian of the aerial photographs library at the Scottish Office, Harry Jack. who had a set of 10”x 8” black and white photographs made from them.

Note: In the late 1980sa few prints of these images, in which railway lines were prominently featured, formed part of a display at a railway preservation society stall in a Railway Fair in Chester Street, Edinburgh.

This done the original glass plate negatives were returned to Lothian Regional Council.

Harry then tried to find out more about the shots like, when they had been taken and who had taken them, but with little success. The only possible clue he unearthed was the name ‘Hobart,’ written in pencil on a file in the Scottish National Reference Library, containing a few copies of some of the photographs.

There was a family of photographers of that name listed as practicing in Edinburgh in the “Photographers of Great Britain and Ireland 1840 to 1940″, website but here is nothing more there than the listing: Hobart & Co., A. W. Hobart, J. W. Hobart and Robert Hobart.

The Edinburgh and Leith Postal directory of 1943-1944 shows an entry for Hobart, Rev., Professor Robert Reid M.A., D.D., as living at 10, Blackford Avenue which might be worth following up.

Harry also searched through his library to see if there were any earlier comparable oblique photos of Edinburgh and found none. Although he did find vertical images from 1927 onwards, the earliest obliques images he found were those taken by a Mosquito, not long after W.W.2.

N.B.

All of this was done before the massive Aerofilm Ltd. collection of aerial photos was incorporated into Historical Scotland’s Air photograph library’s catalogue in 2007

I have seen copies of other photographs which reflect the characteristics of and seem to fit in with those of this series which suggests that our set is not completes.

MY CONTRIBUTION

I was born in 1934 and have lived in Edinburgh for all of my life.

During my formative years my father, who walked everywhere and who had a passing interest in history, enjoyed visiting interesting places in town. And, because he always took me with him everywhere he went, I soon became very familiar with the town in general. (I still have visions of him reading his copy of Grant’s “Old and New Edinburgh”)

So, because urban development grew at a much slower pace then, than it does today, when I looked at the 1930’s images I recognized many of the streets and buildings as those I walked along with my father, it was therefore obvious to me that little had changed since the photos were taken.

Cassell’s Old and New Edinburgh book by James Grant – I have two different copies, as shown above.

In later life as a civil engineer. I regularly used stereographic air photographs to investigate some of the projects I was working on. My principal source of these images was The Scottish Office Air Photograph library in York Place and that was where I met Harry Jack.

On one of my regular visits to his office, accompanied by my colleague and good friend Donald M. Fisher – an eminent geologist and a vastly experienced professional air photographer – Harry showed us the set of 8” x 10” positive prints he had had made from Bill Roberton’s photo-negatives.

My immediate thought was, that apart from their obvious historical significance, the images were an important record of Edinburgh’s urban development and it was essential that they be made available to a wider audience.

Donald, agreed and wearing his professional photographer hat, added that he was impressed by the superb quality of the images.

*

INFORMATION GATHERING

Certainly the idea that the photographs be made more accessible to the public was a good one, but before they could be considered as a meaningful record of the City’s urban and social development, a lot more information about them would be required.

All we knew then was that they were aerial photos of Edinburgh that had been taken a good number of years ago. We had no date, minimal information of exactly where they had been taken and no idea at all about who had taken them.

Before we could even attempt to determine a date for the images, we had to find out which areas of the town they showed.

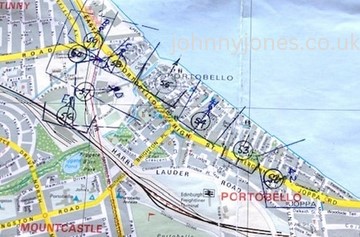

After establishing exactly what each image showed, we plotted the area covered on a map of the town, located the viewpoint of the shot and identified the field of view.

The 1993 Bartholomew’s 1:15000 Coloured Streetfinder Map of Edinburgh proved to be an excellent tool for this purpose.

FINDING OUT JUST WHAT THE IMAGES SHOWED

Even with my long experience of looking at aerial photos and my fairly wide knowledge of the geography of the town, the task of identifying the locations of each image was a particularly time consuming exercise.

Admittedly some of the centre of town shots were easy to identify and one or two shots already had their location marked up on them.

I was also able to locate a few of the others by recognizing the principal features with in the frame

However, that said, there was still a fair number of images, mainly ones with sparse ground detail, that I just could not place. Gorgie Road & Robertson Avenue from above Balgreen is a good example of this.

DATING THE PHOTOGRAPHS

The pictures themselves, provide a number of clues, in that they indicate the time of year they had been taken, such as:

- The trees are in full leaf.

- Portobello beach is crowded.

- Football matches are in progress at both The Gymnasium (the ground of the now defunct St. Bernard’s F.C.) and at Tynecastle the home Heart of Midlothian F.C.

- Cricket matches are being played on both Bangholm, the Trinity Academy’s playing fields, and on the Meadows,

- The clocks on both the North British Hotel and Chancelot Mill confirms that the images were taken at around 3.00pm.

Taking these factors into account, we know that the only time of year during which both cricket and football would have been played and when the trees would have been in full leaf, is late August or early September. And because both football and cricket matches are being played, confirms that the images were taken on a Saturday afternoon in late summer.

Some further evidence that proved to be useful

- It can be seen that the demolition of the Bridewell – the Old Calton Jail, the site of what is now St Andrews House – is well advanced. Records show that this was started in 1929 and I managed to find a photograph in ‘The Scotsman’ archive dated August 1930 which showed the old prison site to be in a similar state of demolition to that of our old photograph.

- It is also evident that work has not yet started on the construction of the open air pool, alongside the Power Station in Portobello. The ‘Porty pool’ was opened in May 1936.

- The old canal basin on Lothian Road has been filled in, to produce the gap site now occupied by Lothian House.

- One of the most significant pinpointing clues was the state of development of the Corporation housing scheme at Redbraes. In our photographs this site is at a very early stage of construction: the warrant for the first 108 houses is dated 2 May 1930 and the one for the remainder was passed on 7 July 1930. Normally work would commence very soon after the warrant was issued. This provides us with a very narrow envelope of time.

Taking all of the above into consideration and by dating the stages of construction of other new buildings and the demolition of some of the old ones throughout the photographs, it was, bit by bit, possible to narrow down the time envelope of when they were taken, to the year 1930.

It is therefore my considered opinion that these black and white photographs were taken on a Saturday afternoon in August 1930.

As already stated (see my previous post), photographs from the air have been around for some time and I’m fairly sure that any aerial images of Edinburgh which predate these ones – including the famous Alfred Buckham one from the early 1920’s (below) are either singletons or very small isolated groups and do not exist in any great numbers.

IDENTIFYING THE ORIGINAL FLIGHT PATH

On close examination of the photos it can be seen that the pilot flew on a South to North path, thus allowing the photographer to take most of his shots with the sun behind him, i.e. aiming eastwards.

Then it struck us that it would be a good idea to take present day images, for comparison, from as near as possible to the same viewpoint and to consider presenting the two – side by side – with appropriate descriptive text – in book form.

This meant finding out who, if anyone, held copyright of the images –That book did not happen!

THE 1993 COLOUR OBLIQUES

In February 1992, although I was fairly sure that the black and white images were no longer controlled by copyright law, I approached Ben Ireland, the then Deputy Director of Lothian Regional Councils Highways Department, to ask him how I might get permission to use them. Ben very kindly obtained this permission for me, in the form of a letter, from the Chief Executive of the Regional Council who also confirmed that the images were now in the public domain, so we could now carry on with our plans.

To re-capture the position and alignment of the 1930’s photographs, Donald and I spent a good deal of time on the drawing board, determining the point above which the photos had been taken and the resulting field of view. Then by plotting these, image by image, on an up to date copy of Bartholomew’s 1:15000 Street-finder map of Edinburgh, we were able to identify the general area of each shot.

It soon became apparent, that we were, in fact, recreating the 1930 plane’s flight paths.

Maps used to identify ground features on the photographs

- 1931 revision of the Ordinance Survey six inch to the mile map of Edinburgh (6 sheets)

- 1924 A. Horseburgh Campbell the City Engineer’s four inch to the mile map of ‘The City and Royal Burgh of Edinburgh’

- . 1917-1918 John Bartholomew’s six inch to the mile The Post Office Plan of Edinburgh, Leith, and Portobello with suburbs

With the flightpaths determined we then organized our 1993 sortie.

THE FLIGHT

The new photographs were taken in the early afternoon of Tuesday 17 August 1993, (Around the same time of year as the originals)

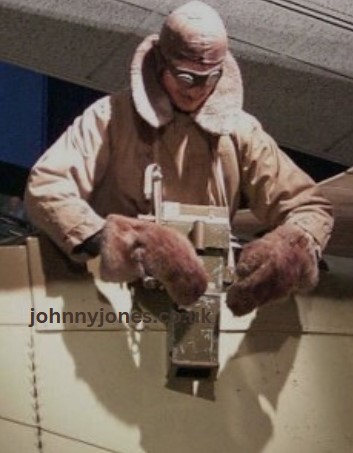

Pilot Pete Clunas took our P.L.M. Squirrel helicopter to a height of 1500ft.then, with myself acting as navigator, Donald Fisher – using a hand held Hasselblad camera, – shot a minimum of 3, but more often than not, closer to 6 slightly overlapping images of each site.* The closest match between these shots and the original, would then be used in any future book.

*This allows the images to be seen in 3 dimensions when viewed through a stereoscope.

As the ‘local’, it was my task to guide the pilot – through the on board radio communication head set – to a position over the spot from where the 1930 shot had been taken. Once there, I would indicate to the photographer his shot alignment and point out to him the other recognizable features on the ground.

The photographer would then compare what he was seeing with the original and compose his shot. This turned out to be no easy task, as many of my points of reference had either disappeared or been altered since 1930, so my fixing of our exact position and orientation often took some time.

At the same time as I was trying to help the photographer to get his eye in’ for his photograph, I was telling the pilot where I wanted him to go next.

While I was doing this the photographer was also talking to the pilot, fine tuning the position for his current shot. All these instructions were being conveyed through the in-flight communication system!

Up in the air seeing what I was seeing was spellbinding and I continually found my eye straying from what it should have been be looking at. And, because we were travelling a substantial distance in no time at all, any such lapse in concentration meant that I lost my reference points and had to re-orientate.

This took me time to get used to and, to begin with, we had to go round again and again to get the shots we required.

Meanwhile at the back of my mind I was forever conscious that helicopter time does not come cheaply.

However, apart from my being told off by the professionals for interrupting their well drilled fine tuning operation, the system worked reasonably well and we completed our assignment in just under three hours.

Although the final results were excellent, the comparison book did not happen.

Asides

- In 1993, while we were hovering in the airspace above Saughton Prison taking a number of shots from an identified shot position, our radio waves were bombarded by increasingly aggressive demands for us to “get that******* helicopter away from there.” Clearly we had caused the prison authorities some concern, However in our defense we were only trying to re-fly and photograph the route flown in 1930.

- On the 10th September 1993, one month after our sortie, the P.L.M. Squirrel helicopter that we flew on our photo session crashed and was written off. The pilot Pete Clunas had a lucky escape and although he suffered severe back injuries, he survived. A mechanical failure was identified as having caused the engine to cut out, leading to the crash. In the subsequent air accident enquiry Pete was absolved from blame

- Donald and Pete were a very experienced team but I was a novice so at times I felt that I was getting in the way.

BASIC COMPARISON OF THE PHOTOGRAPHS

My colleagues had, from experience, estimated that the originals had been taken from a height of around 800 feet. However, our minimum legal flying height was fixed at no lower than 1500 feet. The result of which was being that we could not exactly replicate the shots taken during the earlier flight, which meant that each of the 1993 series of shots covers a significantly greater area than that of the 1930 images.

Originally we did try to match the frames of the two sets of images but to cut off large areas of the later photographs, just to make things appear neat and tidy, seemed wasteful.

There is no doubt in my mind that by leaving them as they were will be of far greater interest to future generations, who will have had an accurate record of the larger areas of the town made available to them.

Since these early photographs were taken, considerable changes have taken place. Many of the landmarks of that time have disappeared and, in some instances, have been replaced by other landmarks.

The Results

I was now able to trace the infilling and development of what had been open spaces, identify the changes to the general infrastructure and the lines of communication – particularly the loss of public transport lines which had existed then.

Less evident were the changes in the New Town, they are still there, but perhaps more subtle than those seen in the suburbs, where the urban sprawl and the loss of open space is more obvious.

However all of the effort has not been in vain, as the Edinburgh Life Magazine is currently – and have done so since October 2023 – been running a series of articles featuring side by side copies of the 1930 and the 1993 photos with identifying descriptions underneath.

The fascinating experience of my helicopter ride let me see what our town looked like from above in 1993 and highlights the stark changes that have taken place in our City, when we compare them with the photos taken on that summer’s day in 1930.

Top left – Peter Clunis; Top right – Donald Fisher

Top Row – Peter Clunis (Helicopter Pilot); Donald Fisher (Photographer); Bill Roberton (Photographer) and Bottom Row – John A. Jones (Navigator).

PLANES USED FOR EARLY AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHS

If you have got this far, thank you for staying the course. Look out for the follow up article in October 2024.

If you have any questions about the foregoing, I will be only too happy to try to answer them.

If you have any information that you think might add to this article, I will be delighted to hear from you.

Just an observation!!

Stenlake Publishing are looking at doing a reprint. If enough people show an interest it could well tip the balance in favour of it happening.

John A. Jones aka Johnny Jones – September 2024

September/October 2024 Edition of the Edinburgh Life magazine:

Realmente fascinante.

LikeLike

Fascinating and appreciate the dedication of those involved.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Could drones be used to update the photographs from 800 feet?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Peter, a very good idea, thank you for this. Best wishes, Johnny

LikeLiked by 2 people

I enjoyed this immensely Johnny. It must have been a very interesting and consuming task to undertake, and was definitely well worth while. Those early pioneers of aerial photography did a tremendous job under very difficult circumstances and it’s almost an obligation on the part of the printers to reprint your book just to acknowledge their (and your) contribution to recording the history of Edinburgh.

LikeLiked by 2 people