The Edinburgh Life Magazine is currently publishing a series of black and white Aerial Photographs taken in 1930 and comparing them to a series of my colour photos taken, from the same view point, in 1993 .

With this in mind I offer the following post as a snapshot introduction to the history of Aerial Photography. – Johnny Jones.

MAN’S FIRST FLIGHT

It was in October 1783 that human beings took the first manned flight. This was done in a tethered hot air balloon i.e. anchored to the ground by ropes. However it was not until, a month later, 21st November that man ascended in an untethered balloon to embark on the voyage that is now accepted as the “first flight by a human being”.

MAN’S FIRST POWERED FLIGHT

On December 17, 1903, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina – after four years of research and development – Wilbur and Orville Wright (with Orville at the controls) flew the Wright Flyer and by doing so achieved the first successful manned flight of a heavier than air flying machine. This event provided the world with a new platform for photography from the air above.

This system was later used extensively by the Royal Flying Corps, formerly the R.A.F. during WW1, who continued to do it after the war and still do to this day.

The first ever successful photograph from a balloon is believed to have been taken in October 1858 above the French village of Petit-Bicêtre by Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, known professionally as Nadar (pictured above) and who in that same month took out a patent on a “système de photographie aérostatique.”

Note: All of the early air photos are oblique images.

The glass plates used during his earlier experiments at balloon photography, had all come out mysteriously blackened, the problem being that the hydrogen sulphide escaping from the balloon had reacted with the silver iodide coating on his plates’-which he had by then finally resolved.

Unfortunately, Nadar’s 1858 balloon photograph is not known to survive today. It’s true that a photographic print (shown below) held by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France has a caption that translates as “First Result of Aerostatic Photography obtained at the altitude of 520 meters by Nadar 1858”. However, this image – see below – is wrongly labelled. It was actually taken ten years later over Paris, during the Exposition there in 1868.

The oldest known surviving aerial photographs date from an ascension over Rhode Island, on August 16, 1860, by the pioneer aeronaut Samuel Archer King and the Boston-based photographer James Wallace Black. During the ascension, Black secured two photographs, both of which unfortunately contained flaws.

PHOTOGRAPHS OF BOSTON TAKEN FROM A BALLOON.

Extract from, “The World’s Oldest Aerial Photographs” by Patrick Feaster

“A few months ago, I picked up a photograph on eBay showing a view of a town with a body of water in the background and evidently taken from a great height. The seller described it as an ‘early aerial photo ca.1860 from a balloon’ but was not sure quite when it had been taken or where, although it had reportedly turned up among the effects of a family from Hingham, Massachusetts.

Information has now come to light that reveals that these images were taken during King and Black’s second flight.

“The experiment of photographing the city and its environs, undertaken on Saturday by Mr. Black, of the firm of Black & Batchelder, assisted by Mr. King, the aeronaut, produced the most satisfactory results. The idea that it was possible to get photographic pictures of the earth from the sky first occurred to Dr. W. H. Helme, of Providence, who, having interested Mr. Black on the subject, the two made an ascension from Providence a few weeks since, to make a trial in the “high art.”

Then, as on Saturday, the balloon Queen of the Air furnished by Messrs. King & Allen, was confined by a cable at an elevation of 1,200 feet.”

The print itself is an oval vignette mounted on a card-stock backing, considerably larger than the one shown in the above scan, with only a tiny and frustratingly uninformative imprint on the reverse: “PHOTOGRAPHED BY.”

It’s an intriguing image, and my quest to learn more about it has drawn me into the adventuresome early history of aerial photography—a history which I’d now like to share with you in turn, and in which, the above photograph turns out to be significant.

I couldn’t find this second photograph anywhere online, but it’s reproduced in William F. Robinson, A Certain Slant of Light: The First Hundred Years of New England Photography (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1980), p. 56, which was my source for the scan below.

MofMA has a print made from the second negative as well, but with an important difference: it’s been cropped to an oval vignette. This implies that Black considered the image at best a partial success, since the purpose of the vignette could only have been to make the print more aesthetically suitable for exhibition or sale.

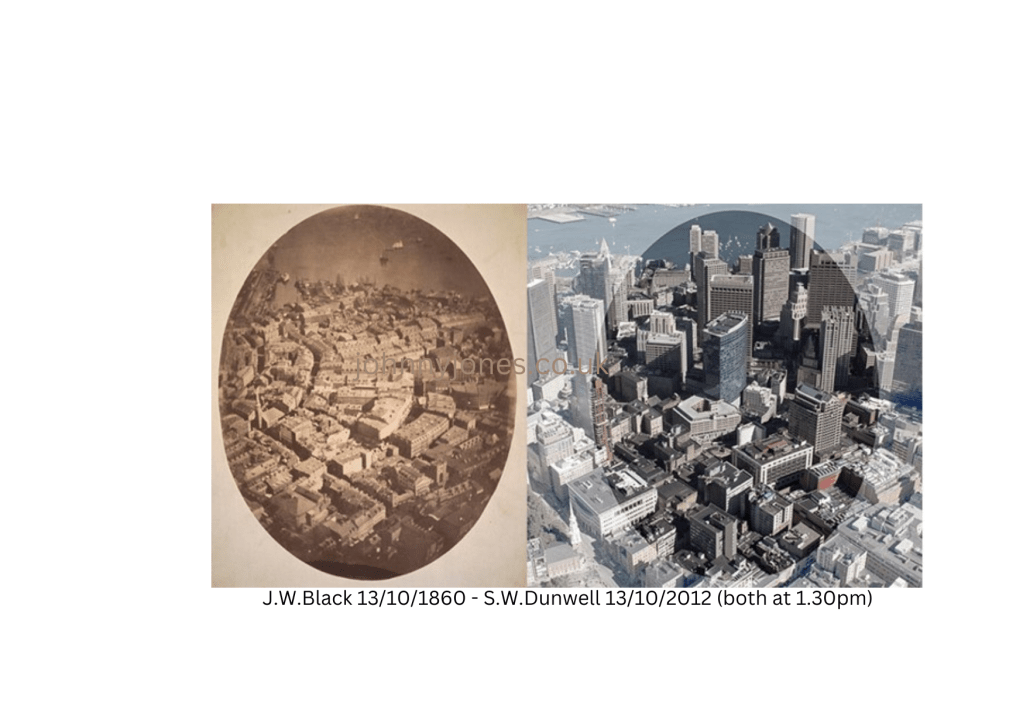

The foregoing three aerial photographs taken from above Boston on 13/10/1860 still exist. On the map below I’ve marked the approximate fields of view represented by each photograph.

Red Envelope shows photograph by J.W Black 16/10/1860

Green Envelope shows photograph re-taken by S. W. Dunwell in 13/10/2012.

Blue Envelope Note: Another image, taken during the same 1860 ascension—a view of Charlestown.

The Huntington Library apparently holds a print of this, but as far as we know it hasn’t been published anywhere.

***

As the technology of photography advanced—with roll film, lighter cameras, and long shutter releases—it became possible to fix cameras to unmanned flying objects.

Between 1887 and 1889, Arthur Batut, using a kite, a camera, and a fuse trigger, took aerial shots of the South of France.

George R. Lawrence used a similar technique from two thousand feet up, to photograph the damage done by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

In 1908, Julius Neubronner, who had used carrier pigeons in his work as an apothecary, filed a patent for a miniature camera that could be worn by a pigeon and would be activated by a timing mechanism.

The French also used pigeons to capture photos showing the position of the German army during the First World War, most notably at the Battles of Verdun and the Somme.

After the Second World War, according to the agency’s website, the C.I.A, developed its own pigeon camera. The details of the camera itself remain classified.

During and immediately after the First World War, archaeologists were already using existing aerial pairs of photographs, to investigate (in three dimensions,) sites and landscapes of interest in Macedonia, Romania, Mesopotamia and the deserts of the Near East. For example, in 1919, in a paper titled ‘Air photography in archaeology’, Lieutenant-Colonel G.A. Beazeley published his discovery of an ancient city on the Tigris as being the result of using aerial survey for mapping.

In a different type of landscape, with less imposing historical remains, O.G.S. Crawford working with stereo air photographs taken by the Royal Air Force produced maps of areas of upstanding archaeological landscapes in southern England. His results were published in an Ordnance Survey Professional Paper in 1924 that included analytical comments about aerial photographs and maps showing extensive areas of the country he had plotted. Also in that paper is a summary of Crawford’s work in the Stonehenge vicinity a venue that had been plough-levelled but become visible due to the differential crop growth, shown up by RAF photographs taken in 1921.

Other photographs taken at around that time showed indications of buried archaeological features through shadows and their effect on cereal crops. Crawford identified a fair number of banks and ditches through this methodology. He named them ‘crop sites’ or ‘crop marks’ and these phenomena led to the huge success of aerial observation for archaeological purposes in temperate lands during the next 100 years.

Crawford himself undertook an airborne project with Alexander Keiller in 1924, when they set out to photograph many of the upstanding sites in central-southern England (Wessex). A selection of their aerial photographs illustrated in their 1928 book, contained detailed analytical field surveys of the selected sites. This was the first display of man’s ability to illustrate past features of specific areas by using stereo aerial images.

Further aerial photography in the Near East was undertaken by Erich Schmidt (1940) “Flights over ancient cities of Iran.” sponsored by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago on whose web site Schmidt’s photographs can be seen.

Between the two World Wars, the journal Antiquity, founded by Crawford in 1927, promoted the uses of aerial photographs on a world-wide basis, in almost every issue.

Through his contacts in Britain, Crawford was able to ensure that many of the sites photographed by the RAF were examined on the ground, often through excavation. This gain in knowledge on British sites is one key element that may have been responsible for the fact that now aerial evidence is accepted as valid by itself in the U.K. but treated with some suspicion in other countries.

By the late 1920s, Crawford had an arrangement with the RAF that pilots would target archaeological sites during normal operational navigation exercises and in his role as Archaeology Officer for the Ordnance Survey these photographs would be passed to him.

This enabled him to build up what is now known as the Crawford Collection, now held in British national collections.

Still in Britain, in 1933, a Major Allen, inspired by one of Crawford’s books, made his own cameras and began flying and photographing sites in the Thames Valley (and later other places). His aim, he wrote, was to discover new sites which has been one of the driving forces behind many later aerial photographers. Allen used some of his discoveries to create two maps of Thames valley locations which were published in 1938 and 1940. His photographs captured the rural landscape when it looked ‘soft’, before the advent of industrialised farming. These images should also be valued for their archaeological content. Copies of his photographs can be seen on Ashmolean Museum’s website.

The advent of World War Two stopped any further exploration and development in aerial work as, almost everybody, apart from Derrick Riley in England, who was able to use some of his RAF test flights to observe, record and sometimes photograph sites close to his airfield bases.

Riley published five papers during or just after the war, one of which laid down the basic rules and definitions about how sites were visible from above. He then appears to have faded from the aerial scene.

Immediately after the end of the war, John Bradford and Peter Williams-Hunt, both archaeologists and serving photographic intelligence officers in Apulia, Italy, undertook their own aerial survey (using RAF aircraft and equipment) to cover a considerable area of the Tavolieri a region dense in sites from Neolithic to Roman times.

Bradford was responsible for most of the publication as Williams-Hunt had moved to SE Asia where he retained (and published) his aerial interests. Bradford’s work culminated in a book (1957) which included theory, method, and case studies relevant to the use of aerial photographs in the examination of ancient landscapes.

Alfred Buckham, born in 1879, was one of the greatest of the first generation of aviators, taking to the sky against doctors’ orders and surviving nine crashes.

A reporter of the Daily Express writes about him: ‘Above is a shot of one of the world’s earliest aerial images, taken from a plane by a daredevil pilot who was so passionate about his photography that he risked his life to capture many of his breath-taking shots. To better capture a scene, he often tied himself to his plane by a scarf and stood up in its open cockpit.’

In 2007 when Aerofilms’ was facing financial difficulties, its extensive archive collection was acquired by the nation.

The catalogue of ‘Britain from Above’ allows users to download images for free and share personal memories, as well as adding information to help enrich the understanding of the stories behind each of the images.

They can also help identify the locations of several “mystery” images that have left the experts stumped.

The images were conserved, catalogued, and digitised by the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), their sister organisation in Wales, and English Heritage.

Due to their age and fragility, many of the earliest plate-glass negatives and prints were said to be close to being lost forever.

By the end of the project in 2014, some 95,000 images taken between 1919 and 1953 had become available online, showing the changing face of modern Britain.

Rebecca Bailey, head of Education and Outreach at the RCAHMS, has said: “The history of Aerofilms is inextricably linked to the history of modern Britain.

“Between 1919 and 1953, there was vast and rapid change to the social, architectural, and industrial fabric of Britain, and the Aerofilms images provide a unique and at times unparalleled perspective on this upheaval. We hope that people will be able to immerse themselves in the past through this website, adding their own thoughts and memories.”

I hope you enjoyed reading this,

Johnny

**************************************************************************************

Caveat

The information provided and the opinions expressed here are the author’s personal interpretation of the featured events he has accessed. It must also be recognised that modern search methods are continuously finding and re-interpreting new information.

Future posts will include.

The Birth of Stereographic Photography and The Team behind the 1993 stereo air photos.

Hi Johnny,

What a fascinating journey through the history of aerial photography! It’s incredible to think about how far we’ve come, from those early balloon photos to the advanced techniques we have today. Your project comparing the 1930s and 1993 images must offer a striking perspective on the changes over time. Thank you for sharing this rich history—it’s a reminder of how innovation and determination have shaped the way we see our world from above.

Looking forward to seeing more of your work!

Best,

Mike

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Mike, there is a follow up article coming in October which may be of interest. Best wishes, Johnny

LikeLiked by 2 people

I will look it up

LikeLiked by 2 people

Fascinating. I had a uncle who was an aerial surveyer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Johnny, for this fascinating insight into aerial photography. If only we could bring back those early pioneers and let them loose with digital cameras and drones. I’m sure they could still teach us all a great deal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to see you back around, Johnny.

LikeLiked by 1 person